New research published today by the Nuffield Foundation shows that divorce law in England and Wales is incentivising people to exaggerate claims of ‘behaviour’ or adultery to get a quicker divorce.

In practice, these claims cannot be investigated by the court or easily rebutted by the responding party, leading to unnecessary conflict and a system that is inherently unfair.

Divorce affects more than 100,000 families in England and Wales every year. If separating couples want to get divorced without waiting for two years (or five if the other person does not consent, as with the recent case of Owens vs Owens), one person must submit a petition detailing how the other is at ‘fault’. In 2015, 60% of English and Welsh divorces were granted on adultery or behaviour. In Scotland, where a divorce can be obtained after one year if both parties agree, this figure was 6%.

The research, led by Professor Liz Trinder at the University of Exeter and funded by the Nuffield Foundation, is the first empirical study since the 1980s of how the divorce law in England and Wales is operating. The researchers recommend removing fault entirely from the divorce law and replacing it with a notification system where divorce would be available if one or both parties register that the marriage has broken down irretrievably and that intention is confirmed by one or both parties after a minimum period of six months.

The study included interviews with people going through divorce, focus groups with lawyers, observation of the court scrutiny process and analysis of divorce court files, coupled with a national opinion poll and comparative analysis of divorce law in other countries.

Divorce petitions are often not accurate descriptions of why a marriage broke down and the courts make no judgement about whether allegations are true.

In a national opinion survey, 43% of people who had been identified as being at fault by their spouse disagreed with the reasons cited for the marriage breakdown and 37% of respondents in the court file analysis denied or rebutted the allegations made against them by their spouse. In practice these rebuttals are ignored except in the rare cases where the respondent is able to defend the case (as in the recent case of Owens v Owens). The court did not raise questions about the truth of a petition in any of the 592 case files analysed, despite evidence that respondents disagreed with the claims made.

The removal of legal aid for all but a minority of cases (e.g. domestic violence), means that in practice, few people have the financial resources to defend themselves. For these people, getting divorced means accepting that the court’s decision relies on a version of events they do not consider to be true.

Uncertainty about what constitutes unreasonable behaviour undermines the principle for the rule of law to be ‘intelligible, clear and predictable’.

In the 1980s, 64% of behaviour petitions were based on allegations of physical violence, but this has now fallen to 15%, indicating that there has been a large drop in the expectations of the courts as to what is needed to prove ‘behaviour’ in the last 30 years.

Despite this drop in the threshold, many lawyers and members of the public do not know exactly how low it is. This uncertainty means some lawyers are filing stronger and potentially more damaging petitions than necessary, while people who cannot afford a lawyer may think they have to wait out long separation periods because they do not ‘qualify’ for the faster fault-based divorce.

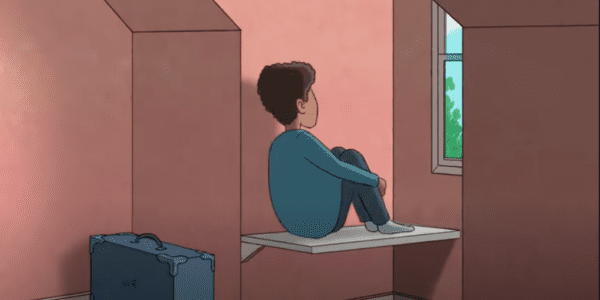

The use of fault may trigger, or exacerbate, parental conflict, which has a negative impact on children.

In the national survey, 62% of petitioners and 78% of respondents said that in their experience using fault had made the process more bitter, 21% of fault-respondents said fault had made it harder to sort out arrangements for children, and 31% of fault-respondents thought fault made sorting out finances harder.

When interviewed, both petitioners and respondents gave examples of how the use of fault, mainly behaviour, had had a negative impact on contact arrangements, including fuelling litigation over children. Some described threats to show the petition to children.

Divorce law in England and Wales is out of step with Scotland, most other countries in Europe, and North America.

The heavy reliance on fault in England and Wales, used for 60% of all petitions, is ten times that of our closest neighbours in Scotland and France. However, the researchers do not advocate adopting incremental reform of the law based on the Scottish system, partly because using fault would still remain the quickest option (which could incentivise continued reliance on it), and partly because of the differences in wider factors that could not be replicated in England and Wales without major reform of other areas of family law.

Fault does not protect marriage or deter divorce

The study found no empirical support for the argument that is sometimes made that fault may protect marriage because having to give a reason makes people think twice about separating. In fact the evidence points the other way: analysis of case files shows fault was associated with shorter marriages and shorter gaps between the break-up of the relationship and filing for divorce.

Professor Liz Trinder said: “This study shows that we already have something tantamount to immediate unilateral divorce ‘on demand’, but masked by an often painful, and sometimes destructive, legal ritual with no obvious benefits for the parties or the state. A clearer and more honest approach, that would also be fairer, more child-centred and cost-effective, would be to reform the law to remove fault entirely.”

“There is no evidence from this study that the current law protects marriage, and there is strong support for divorce law reform amongst the senior judiciary and the legal profession. We recommend removal of fault so that divorce is based solely on the notification, and later confirmation, by one or both spouses that the marriage has broken down. This should be a purely administrative process with no requirement for judicial scrutiny – in the twenty-first century, the state cannot, and should not, seek to decide whether someone’s marriage has broken down.”

Teresa Williams, Director of Justice and Welfare at the Nuffield Foundation said: “It is essential – perhaps now more than at any time – that public trust in institutions is maintained. The law is at serious risk of being brought into disrepute by the mismatch between the divorce law in theory and what is actually happening in practice. In addition, there is a discrepancy between the law and the realities of people’s experiences. Relationship breakdown and separation can be complex and messy. It cannot be readily categorised or date stamped, and the perspectives of those involved can differ legitimately.

“The dominance of ‘fault’ within divorce law is at odds with the thrust of wider reforms in the family justice system, which have focussed on reducing conflict and promoting resolution, both of which play a role in improving the outcomes for the parties, including any children involved.”

ENDS

1. Parliament previously attempted to introduce no fault divorce in the Family Law Act 1996. However this was never implemented because of perceived problems with adding complex procedures to the existing legal system. This means that the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 remains in force.

2. The Nuffield Foundation funds research and student programmes that advance educational opportunity and social well-being across the United Kingdom. We want to improve people’s lives, and their ability to participate in society, by understanding the social and economic factors that affect their chances in life. The research we fund aims to improve the design and operation of social policy, particularly in Education, Welfare, and Justice. Our student programmes enable young people to develop their skills and confidence in quantitative and scientific methods. www.nuffieldfoundation.org.

Related

-

Full report – Finding Fault – Divorce law and practice in England and Wales2MB | pdf | 01 February 19

-

Summary report – Finding Fault – Divorce law and practice in England and Wales648KB | pdf | 01 February 19

-

Technical appendix – Finding Fault – Divorce law and practice in England and Wales390KB | pdf | 01 February 19