New research published today by the Nuffield Foundation explores why defended divorce occurs and examines how cases are dealt with by the courts.

No Contest finds that the great majority of defences arise from quarrels about who is ‘at fault’, but in practice this is not something that can be determined by the courts and most cases are settled, rather than decided by a judge.

In addition, the financial and emotional costs, and discouragement from the family justice system, mean that defending a divorce is not an accessible option for most people. The report concludes that the law is generating disputes and then failing to remedy them, and calls for reform of the divorce law to remove the concept of fault entirely.

The research was led by Professor Liz Trinder at the University of Exeter and is timely given the imminent Supreme Court hearing in the case of Owens v Owens, the only successfully defended divorce case in recent years. The No Contest report is a follow-up to last year’s Finding Fault report, and together, the two reports present findings from the first empirical study since the 1980s of how the divorce law in England and Wales is operating. Finding Fault reported that the law is incentivising people to exaggerate claims of ‘behaviour’ or adultery to get a quicker divorce. These claims cannot be investigated by the court or easily rebutted by the responding party, leading to unnecessary conflict and a system that is inherently unfair.

What is defended divorce?

No Contest focuses on the two per cent of divorces in which the spouse accused as being ‘at fault’ (the respondent) tries to take advantage of their legal right to formally defend allegations that they see as untrue or unfair. Contested cases are important because the court has an opportunity to test what the two parties say, rather than simply being able to rubber stamp applications. The researchers found three major problems.

1. The financial, legal and emotional barriers to defence mean that the majority of respondents do not get the chance to put their side of the story to the court. A third of respondents formally record their disagreement with allegations made against them, but only 2% say they intend to defend and less than 1% actually do. Defending a divorce is technically and emotionally demanding and few can afford the legal fees, typically about £6,000. Family lawyers and the courts generally discourage defence, seeing it as expensive, counter-productive and futile. Respondents are therefore unable to prevent being divorced on the basis of allegations that they think are untrue.

2. The law itself is causing most disputes that result in a defence. The majority of those who do formally defend the divorce are not trying to stop the divorce from happening. Instead they want to give their reason for why the marriage broke down. None of those defences would be necessary if the law did not include fault. Only 18% of people defending were denying that the marriage had broken down. Their motivations varied, but defence could also be misused by those wanting to avoid a financial settlement or trying to retain control over their spouse. In some cases, the spouse appeared to be ‘in denial’ about the breakdown of the marriage.

3. Even defended cases rarely end up in a court hearing. Although those defending are trying to persuade the court to accept the ‘truth’ or justice of their case, the court is focused on compromise, trying to avoid further expense and acrimony for the parties. Almost all cases are strongly encouraged to reach a compromise before a trial before a judge, meaning the ‘truth’ is never established by the court. Only two cases in the report reached a fully contested final hearing, and the court allowed the divorce to proceed in both.

Owens vs Owens: an exceptional case

The Owens case attracted significant media attention in 2017. It is a rare defended case where the husband denied that the marriage had broken down and disputed the behaviour allegations. The trial judge described the allegations as “scraping the barrel” and refused the decree. The Court of Appeal upheld that decision, finding that the judge was not plainly wrong, though noting that the ‘flimsy’ allegations were typical of many undefended petitions that are granted. The decision is being appealed to the Supreme Court and is listed for 17th May.

The need for law reform

The analysis of the 1% of divorce cases that are defended strengthens further the need for law reform identified in the Finding Fault report. The current law does not work well for the great majority of undefended divorces or for the tiny minority of defended cases. The researchers recommend removing fault entirely and replacing it with a notification system where divorce would be available if one or both parties register that the marriage has broken down irretrievably and that intention is confirmed by one or both parties after a minimum period of at least six months. There would be no need for a further procedure for defence under such a system.

The research

The research is based on court file analysis of 300 undefended cases, 100 intend to defend cases and 71 cases with formal Answers to defend the divorce. The case file analysis was supplemented by observation of the court scrutiny process and interviews and focus groups with petitioners and respondents, family lawyers and judges.

Professor Liz Trinder said: “The divorce law is now nearly 50 years old and reform is long overdue. Our interviewees told us how difficult marriage breakdown is, yet the law makes the legal divorce even more difficult than it needs to be. Having to blame one person to get a divorce does not help and in most cases is unfair. And the court is not able to investigate why a marriage has broken down and recognises anyway that it is a fool’s errand. The problem is that there is now a big gap between what the law is in theory and how it works in practice. That is not good for families or for the law.

“While the Supreme Court may find a way to grant Mrs Owens her divorce, the Supreme Court can only interpret the law, it requires Parliament to change it. Reforming the divorce law to remove the requirement for ‘fault’ and replacing it with a notification system would be a clearer and more honest approach, that would also be fairer, more child-centred and cost-effective. In the twenty-first century, the state cannot, and should not, rule on whether someone’s marriage has broken down and who is to blame.”

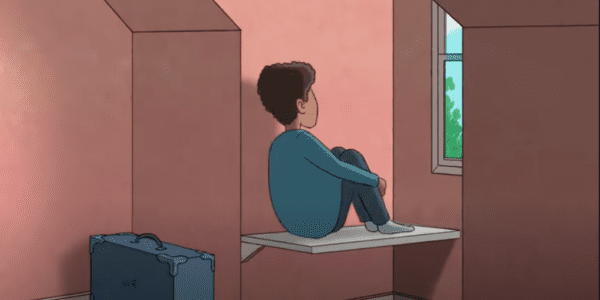

Tim Gardam, Chief Executive of the Nuffield Foundation said: “The current law incentivises people to apportion blame for the breakdown of a marriage, but this research demonstrates that in practice this is a fruitless task and not one over which the justice system can effectively and fairly preside. This mismatch between the law in theory and the options available to people in practice, means that public confidence in the justice system is at risk of being undermined. Professor Trinder’s research shows that the dominance of ‘fault’ within divorce law can exacerbate parental conflict, which has a negative impact on children, and she makes a powerful argument for reforming the law to align with the family justice system’s wider focus on reducing conflict and promoting resolution.”

ENDS

1. Divorce affects more than 100,000 families in England and Wales every year. If separating couples want to get divorced without waiting for two years (or five if the other person does not consent, as with the recent case of Owens vs Owens), one person must submit a petition detailing how the other is at ‘fault’. In 2015, 60% of English and Welsh divorces were granted on adultery or behaviour. In Scotland, where a divorce can be obtained after one year if both parties agree, this figure was 6%.

2. Parliament previously attempted to introduce no fault divorce in the Family Law Act 1996. However this was never implemented because of perceived problems with adding complex procedures to the existing legal system. This means that the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 remains in force.

3. A summary of the October 2017 Finding Fault report and the report itself are available for download at http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/finding-fault-divorce-law-practice-england-and-wales

3. The Nuffield Foundation funds research and student programmes that advance educational opportunity and social well-being across the United Kingdom. We want to improve people’s lives, and their ability to participate in society, by understanding the social and economic factors that affect their chances in life. The research we fund aims to improve the design and operation of social policy, particularly in Education, Welfare, and Justice. Our student programmes enable young people to develop their skills and confidence in quantitative and scientific methods.