22/04/24

6 min read

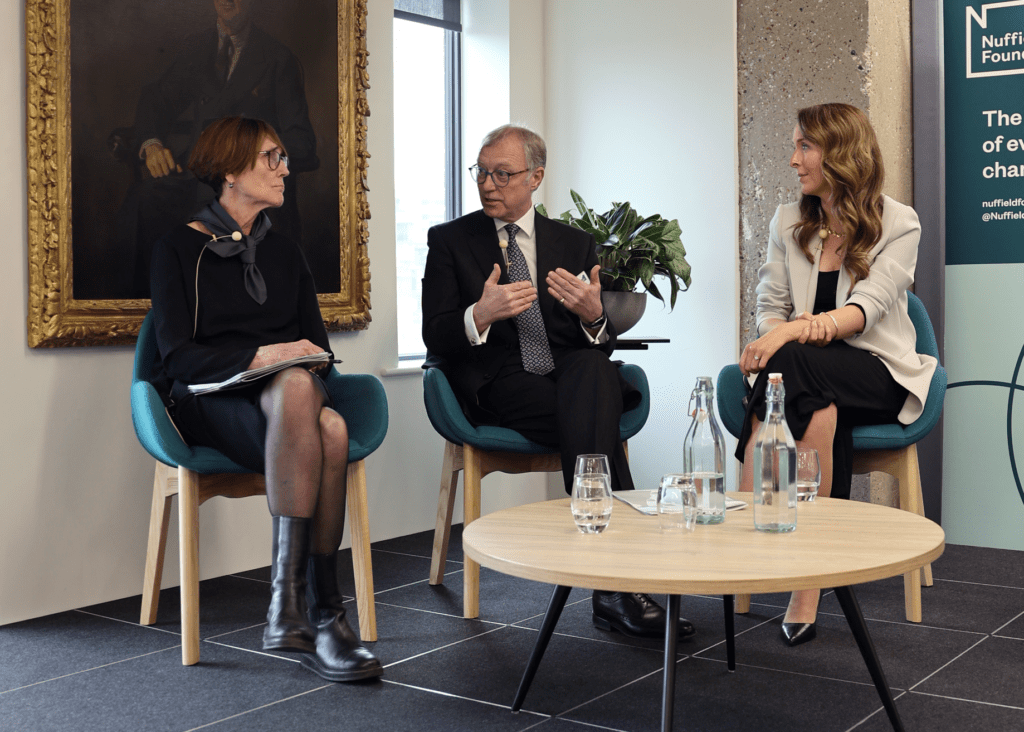

Address by Rt Honourable Sir Ernest Ryder, Nuffield Foundation Trustee, at our Justice conference

The Nuffield Foundation has a purpose which is to advance social well-being.

Our work cuts across education, welfare, and justice. We specifically aim to address the inequalities, disadvantage, discrimination and vulnerabilities people face in justice and consider the ethical implications of systems, processes, technologies and decision-making.

In this, our 80th anniversary year, our challenge is to ask how we can build and maintain the effective, accountable and trustworthy institutions that we need to support our society and its communities and maintain the legitimacy of the rule of law as the glue that holds us together.

Justice systems are not simply the buildings in which the judiciary sit, or the quality of the judgments they undoubtedly produce. They are much more. At the very least there are, in addition, three aspects that I suggest are of critical importance to their effectiveness:

-

First, the observational or performative perceptions of trust, respect and confidence in these systems by people and their communities, who will often have different and sometimes conflicting or incommensurable values that need to be respected if not resolved.

-

Second, the impact of those systems on people and their communities as measured by data on outcomes that are quantifiable so that we are able to understand access to justice and whether the systems are effective in addressing inequalities, disadvantage, discrimination and vulnerability and answer the question whether there is in fact equality before the law.

-

Third, the quality of our governance of those systems. The leadership of justice is a partnership between the Executive or Government, including the devolved administrations, and the Judiciary. That leadership has a relationship with Parliament that reflects the constitutional principle of accountability while respecting the separation of powers. Without that delicate balance being demonstrated there will be a democratic deficit in the exercise of power.

We have over time developed careful conventions to regulate and re-calibrate our governance: for example:

- Constitutional norms such as sovereignty, accountability, separation of powers, independence of the judiciary and access to justice;

- The principles of the Rule of Law which are well described in international instruments; and

- Ethical standards and codes of conduct, for example concerning independence, impartiality and integrity.

I would suggest, however, that these are not in themselves enough because they do not cause us to measure outcomes, perceptions, in particular trust, and the effect of inadequate governance. The impact of these critical components is most obviously experienced when systems are inadequately resourced so that access to justice is adversely affected with the consequence that the individual is unable to obtain an appropriate, timely and affordable remedy. The consequence of the scarcity of resources will often be insufficient advice and representation, insufficient judges, a poor quality justice environment both as to place and facilities and insufficient investment in training, development, diversity and leadership and management across the justice sector.

Justice that is delayed by backlogs that are a consequence of inadequate funding and inadequately addressed structural questions leads to justice being denied for some of our users. There is an urgent need to go beyond our principles and judgments and examine the effectiveness of our arrangements. There are real concerns about the political leadership of justice and its commitment to the Rule of Law, not I emphasise by individual justice Ministers, although there have been exceptions, but by Government generally, its understanding of constitutional issues, the impact of policies on people and their communities and the effect of inequality and inadequate resources which are questions of legitimate concern.

It is now 20 years since the government of Tony Blair embarked on a new constitutional settlement. Between 2004 and 2008 two Acts of Parliament changed the way that the constitutional partnership between the Executive and the Judiciary was to be led and managed. The Constitutional Reform Act 2005, the Tribunals Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 and the various constitutional instruments that are associated with that legislation: Concordats, Frameworks and Agreements, transferred executive functions to the senior judiciary, in particular from the Lord Chancellor.

The administration of justice and the justice systems that exist had always been a partnership between the Executive and the independent Judiciary, with at least a nod to the constitutional principles of accountability and sovereignty in the way those two limbs of the State engaged with Parliament but the consequence of the changes that took place between 2004 and 2008 remain both poorly understood and researched.

The heads of jurisdiction or chief justices became Presidents of their own courts and tribunals and, as a consequence, executive responsibilities were transferred to them. Statutory duties were imposed on them, and organisational changes were put in place in an attempt to match the strategic and operational functions with capabilities that were intended to help them to discharge those duties.

The changes were so significant that it was necessary to put in place Framework Agreements to regulate the new partnership and reflect the power vested in both the Lord (now Lady) Chief Justice and the Senior President of Tribunals to address Parliament should the arrangements become ineffective. That power has never been used not least because it would bring the partnership to an end but the tensions underlying the same can readily be ascertained from the annual funding and major projects discussions that occur between the senior judiciary and Ministers and their representatives. Let us not forget that on one occasion since the constitutional settlement the arrangements did not work and the questions that arose were not settled until the landmark judgment of the Supreme Court in the UNISON case.

I am not criticising the senior judiciary for the state of justice or the effectiveness of our justice systems. Far from it. The time, energy, strategic and operational skill that has been put into the multiplicity of boards, committees, agency bodies, bilaterals and trilaterals has been notable. It is a major endeavour supported by a skilled Judicial Office. I am equally not criticising His Majesty’s Courts & Tribunals Service or their equivalents in Scotland and Northern Ireland which are the delivery bodies responsible for justice systems. HMCTS in England and Wales has been served by dedicated Chief Executives, senior leadership teams and board members. The problem is systemic.

Justice and the Rule of Law are not regarded as political priorities until something goes wrong. There are few effective environments in which justice systems and their effectiveness are discussed in a transparent and informed way. Justice Councils are notable exceptions, but they do not have the infrastructure of think tanks or the research-intensive bodies we have here at the Nuffield: the Family Justice Observatory, the Nuffield Council on Bioethics and the Ada Lovelace Institute. Bodies that are able to set strategic objectives, commission and help fund research, identify data and its absence, analyse performance and outcomes, provide timely syntheses of good practice and solutions to problems.

There are two very important deficits that have plagued effective delivery for most of the last 20 years: the lack of quality data and the lack of research and analysis of data. In the presentation which follows these remarks, Dr Natalie Byrom will summarise an independent paper that the Nuffield Foundation commissioned from her to highlight these problems with a focus on access to justice. I will not steal her thunder, but the evidence and conclusions are stark.

- Access to legal information and advice is implicit in an individual’s ability to secure access to justice and yet cuts to Government spending and the lack of a coherent plan to provide alternatives to face to face advice have delivered advice deserts.

- Access to formal legal systems is impeded by backlogs, the lack of realistic dispute resolution alternatives and the incomprehensibility of the processes individuals have to navigate.

- Access to a fair and effective hearing is damaged by the lack of representation, and quite insufficient attention to non-adversarial procedures and protections that would help. Justice may be preventative, consensual, facilitative or adjudicative, but it does not always have to be adversarial to be fair.

- Access to a decision according to law is a constitutional right. Where factors presently not analysed because of the lack of data adversely influence that access, for example, ethnicity or post code conceptions of the availability of service delivery, these ought to be surfaced.

- Access to a remedy and enforcement are key to ensuring that justice systems do not make it futile or irrational to bring a claim.

Neither resource rationing nor political ideology, let alone both together, are an adequate basis for the way we lead and / or deliver justice, in particular in circumstances where austerity or ideology reinforce division rather than respect i.e. increase real inequality and / or the perception of inequality.

The consequence is that political initiatives from the Executive do not always hear the voice of users or the independent judiciary or sometimes even Parliament. Partnership working that is necessary to the way justice is delivered becomes fragmented, we lose sight of the good outcomes that ought to be the hallmark of access to remedies and we end up with inadequate advice, systems that are poorly matched to the needs of the user or victim and very real impacts that are both intended and unintended consequences that can damage the Rule of Law.

Scarcity of resources affects the Rule of Law. The poor decisions of users have consequences that include a wide variety of cases where remedies are vital. These may include, for example, financial debt leading to destitution and improper reliance on unregulated and unethical providers; real health and social care consequences; poor family choices with relationship breakdown, domestic violence and public care outcomes having a direct correlation with the impact of scarcity on decision making and relationships; benefits availability and use and much more.

The consequences in relation to criminal behaviour, civil and family disputes, mental health tribunals, benefits appeals and all manor of jurisdictions that are provided by our justice systems are patent but insufficiently researched. We do not identify or measure justice system outcomes, let alone analyse how scarcity and inequality impact on justice system users. We do not know whether we exacerbate those impacts by the ways in which we work including the lack of advice and support.

In simple terms, it is an obligation on leaders of justice systems, including the judiciary, to have regard to how their leadership of those systems impacts access to justice but no-one can operate the levers of institutions, particularly institutions as complex as justice systems, without tools. The lack of research and funding of research into reforms and also into the previously existing non-digital or analogue methods of making decisions, is marked.

The lack of data to analyse is a matter of serious concern and that all has the consequence that there is insufficient strategic thinking or commentary about justice systems and the outcomes for users.

May I finish where I began.

If we are to address inequalities, disadvantage, discrimination and vulnerabilities we must collect the data that is missing and fund research into outcomes. We must provide an evidence base for strategic thinking so that as a consequence we build and maintain trustworthy institutions.

Justice systems deserve our help.

Read the key takeaways from our Justice conference